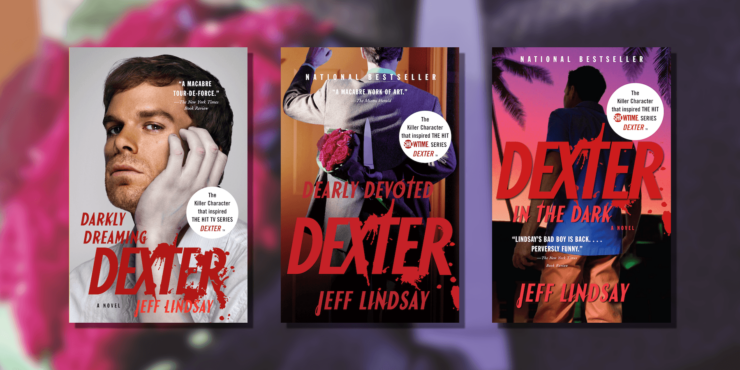

The question is not whether the Showtime series Dexter (which ran from 2006-2013 and was revived in 2020) is better than the eight novels on which it is based. Both were big successes—seven of the books were bestsellers, while the show won four Primetime Emmys, two Golden Globes, and seven Satellite Awards, among other accolades—yet the two versions are only loosely connected. Season one of Dexter was fairly faithful to Jeff Lindsay’s first novel, Darkly Dreaming Dexter, before blazing its own trail, altering storylines and mucking about with characters’ fates. One of the most obvious changes is that the TV series softens the title character from Lindsay’s sociopathic monster to a more personable detective type.

Many critics think this was an improvement. “In the novel,” according to one writer, “Dexter is notably cold and detached—exhibiting many more truly psychopathic tendencies in the way in which he relates to both his victims and other people in his life. By contrast, Michael C. Hall’s Dexter often appears genuinely baffled by the complexities of human emotion while simultaneously demonstrating strong feelings for characters like Deborah [his stepsister] and his erstwhile brother [Brian, who is more integral to the books].” Of course, that’s completely wrong: In every book, Dexter struggles to understand love, forgiveness, white lies, and other rituals of human emotion while also demonstrating observable fondness for his wife Rita, stepsister Deborah, daughter Lily Anne, and stepchildren Astor and Cody.

So the question is not which is better. The question is whether Dexter Morgan, family man, blood spatter analyst, and unrepentant serial killer, is one of literature’s all-time best characters.

The answer, of course, is that he is. Devilishly so.

[SPOILERS for the Dexter novels]

Miami native Jeff Lindsay had written several plays and a few middling novels when he hit upon the idea for Darkly Dreaming Dexter. “It just came to me,” he said in a 2004 interview. “I was speaking at a business booster’s lunch, I don’t know why, and I looked out at the crowd, and thought, ‘Serial murder isn’t always a bad thing.’” He wasn’t a fan of thrillers, which may explain why the books are a bit square-peggish for that category: they were not meant to be conventional cop dramas but deep dives into the mind of a sociopath.

You’re probably thinking that of course Dexter is a sociopath. He kills people. (Note: rather than quibble over the differences between sociopathy and psychopathy, neither are official diagnoses; rather, clinicians group the behaviors associated with both terms under the broader descriptor of Antisocial Personality Disorder. Both terms are mentioned in the books; for the purposes of this discussion, I’ll be using the former). However, lots of people kill people. In every book, there is someone besides Dexter killing people. Does that make them sociopaths?

Not at all. Look at their motives. Dr. Danko in Dearly Devoted Dexter kills for revenge. (Well, technically, he doesn’t kill people—he mutilates them. However, this is murder-adjacent, and certainly not very nice.) Brandon Weiss in Dexter by Design kills out of grief. Doug Crowley in Double Dexter kills to frame Dexter. Samantha Aldovar’s death at the hands of the cannibals in Dexter Is Delicious could be seen as an elaborate suicide. Even the good guys kill. Deborah, a cop, shoots Danco. Cody stabs the Moloch cult leader in Dexter in the Dark. Astor throws a can of soda at Crowley, kicks him in the crotch (twice), and, after he has fallen overboard, runs him over with a boat. Worst of all, Rita—sweet Rita, wouldn’t-hurt-a-fly Rita—shoves Weiss into a whirring table saw, and he bleeds out.

Dexter’s killing is different. He is rarely motivated by emotion (though his desires to kill Weiss and Crowley are motivated by self-preservation, plus a bit of “You talkin’ to me?” vigilante aggression). Instead, he kills for pleasure, and as a form of retribution and a way of cleaning up society according to his own unique code, which is why he targets pedophiles and other creeps who have escaped justice. Still, if we look at the diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder (the technical term for sociopathy), we won’t see “carves people into bologna slices” listed.

What we will see is traits like ignoring right and wrong. Being insensitive. Using charm to manipulate people. Having a sense of superiority. This is because the defining characteristic of a sociopath is an absence of conscience. Sociopaths treat others as tools, obstacles, or playthings. Why? In the words of Martha Stout, author of The Sociopath Next Door, “if you don’t have a conscience, if you don’t really […] love, then the only thing that’s left for you is the game—it’s about controlling things.”

Dexter’s unconscionability comes to fruition in the next-to-last novel, Dexter’s Final Cut. Until then, our hero had hewed to the weirdo-with-a-heart-of-gold trope. He was a killer, but he was our killer. Book seven deconstructs that image. When a television network asks the Miami-Dade Police Department for help in filming its new police procedural, Dexter and Deborah are assigned as technical consultants. Uncharacteristically, Dexter falls in love with the star of the show, Jackie Forrest, with whom he has a guilt-free affair. He is prepared to run off with Jackie to pursue a Hollywood lifestyle, which sounds better to him than traffic jams, homework scrums, diaper pails, paycheck-to-paycheck-ness, and, especially

Rita, with her perpetually fractured sentences and eternal fussing about absolutely everything, and the lines settling into her face as she hurtled into an old age that shouldn’t have come for another ten years at least, and the sense that she always wanted something from me that I couldn’t give her, couldn’t even identify.

Yes, these kinds of frustrations exist in any relationship, but we are supposed to overcome them. What lets us do that? Love. Except Dexter doesn’t feel love. He says it throughout the series. This book is when he shows it.

Of course, there are traits of sociopathy that Dexter doesn’t exhibit. Boredom. An obsession with winning. Criminality (other than killing, he isn’t generally a scofflaw). He has a great relationship with Rita’s kids, Cody and Astor, and when his daughter is born, he moons over her: “A world with Lily Anne Morgan in it is so completely unknown: prettier, cleaner, neater edges, brighter colors […] Poetry flows into my icy cold brain and trickles down to my fingertips, because all is new and wonderful now.” (No doubt this is inspired by Lindsay’s own history as a stay-at-home dad, which he chronicled in a newspaper column called “Fatherhood.”)

And he does have a sort of morality. In a 2004 interview, Lindsay said, “I think Dexter is actually very MORAL—there are lines he will not cross, no matter what. I’m hoping he makes us think a little about what is and isn’t moral, and where the whole idea of a conscience comes from.” Perhaps, then, Dexter is a “mild psychopath,” which Martin Kantor describes in The Psychopathy of Everyday Life as someone whose disorder “has not crowded ordinary successful functioning in the outer aspects of work and social relations entirely out of the picture”—in other words, a low-wattage monster. After all, if you aren’t a monster yourself, you have nothing to fear from Dexter.

Unless you’re his family. I didn’t like Dexter’s Final Cut when I first read it, and after a re-read, I still find it disquieting. Dexter is not just a killer—he’s a jerk. His shabby treatment of Rita creates a permanent rift with Deborah. Astor betrays Dexter, luring him into a trap, which he survives. Rita does not. Her death leads to Dexter’s arrest, leaving Cody, Astor, and Lily Anne parentless.

What if the series ended there? What would it mean if Dexter doesn’t have the chance to redeem himself in the final book, Dexter Is Dead?

Well, it isn’t clear that he does redeem himself. Rita’s still dead, of course. Can’t change that. Cody and Astor don’t appear until the last few pages, when Dexter rescues them from a drug lord. “Knew you’d come,” Cody says. Without that one line of clemency, we could imagine the kids hated him. He has a battlefield alliance with Deborah, but that is only for the purpose of rescuing the kids. It isn’t a true reconciliation. More important, whatever chances Dexter has to make things right don’t matter to him. He doesn’t mourn Rita or miss the kids while in jail. When Deborah visits him, so angry she can barely speak, his only interest is in her ability to get him out.

Buy the Book

Looking Glass Sound

Bottom line: he doesn’t seem to have grown much.

Yet we like him. We even love him. We want more of him. Showtime figured this out and gave us a new series. Will Jeff Lindsay write another book? I’d love it if he did. He does some things that don’t play the same way on the small screen—our unfettered access to Dexter’s inner monologue, for instance. He narrates all the books in first person, meaning we experience the world through his eyes, filtered through his thoughts and reactions. With apologies to Michael C. Hall, the show’s attempts to capture this isn’t quite the same, and can often feel like a clunky device.

Lindsay’s writing is also funnier than the show’s. (My favorite moment is when he catches his departmental nemesis, Sergeant Doakes, snooping on his office computer. “Sergeant Doakes!” he says. “Do you need help logging onto Facebook?”) Finally, it is fascinating to watch Dexter deteriorate through the course of the books. He becomes less charming, less witty, more impulsive. His cockeyed morality slips away, and he eventually bottoms out in Dexter’s Final Cut. A lot of fans dislike that book because Dexter’s douchebag behavior seems unprecedented. I would argue that it was Lindsay’s plan all along. Sociopaths fool society because they seem so normal. That normalcy is an act, however, and it eventually slips. Final Cut is when it slips for Dexter.

In most movies, novels, and TV series, sociopaths are mere foils for the heroic protagonist. We know nothing about them except their misdeeds. We spend little to no time in their heads. Jeff Lindsay flipped the script, and gave us this opportunity: Instead of simple thrillers, his eight Dexter novels are an immersion in one unusual psyche.

They are also studies of us. All of Dexter’s cynical, pessimistic, and confused thoughts and frustrations—about kids, about marriage, about work, about family—are things we all think from time to time and aren’t proud of. The key phrases there are “from time to time” and “aren’t proud of”—our conscience intervenes, helps us find a sense of balance. Conscience and a sense of empathy keep us from behaving like sociopaths, though occasionally it’s a fine line…and that’s precisely why sociopaths continue to fascinate us: this sense of “there but for the grace of God go we.” Sociopaths are a bug in the code, a glitch in the matrix, reflecting the Bizarro World version of our own worst impulses…and we love to read about ourselves.

Anthony Aycock is a librarian and freelance writer who has published in Slate, the Washington Post, Medium, the Missouri Review, the Gettysburg Review, and other venues. See more of his work at his website.